The Big Fuel Crisis of 2000AD

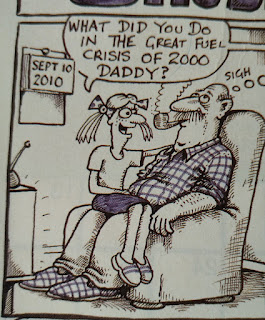

(Picture: Shobba: Truck and Driver Dec 2000)

The sight of queues at petrol stations in September 2021 takes me back to September 2000 and the big fuel crisis.

It’s the same basic set-up. There’s no shortage of fuel being churned out by the refineries. It just can’t get into the service stations quick enough. The big difference is that in 2021 panic buying seems to have made what would have been a difficult situation much worse. There aren’t enough tanker drivers to supply all the petrol stations. But it wasn’t until news got out about the delivery problem that people started panic buying.

In 2000, the tanker drivers couldn’t even get out of the terminals because they were being blocked by farmers lorry and taxi drivers protesting about fuel taxes.

It always sticks in my mind because I’d been over to France the weekend before. French truck drivers had been blockading their own refineries, and in Calais the price displays of the service stations were showing everything at 0.00. In the bright sunlight it all seemed part of the characteristic Gallic bolshiness – a holiday snap to show when I got home. What a surprise to arrive back in gloomy England and find out that “Farmers For Action” were blockading Avonmouth and Kingsbury oil terminals. As the week ground on, more protests erupted and panic-buying generated queues at service stations.

When you’re comparing the 2021 fuel crisis with the 2000 fuel crisis, one thing takes it into the realms of comedy. The British protestors were cheered on by The Spectator, then edited by Boris Johnson (whatever happened to him). The magazine’s editorial said 95% of the public believed fuel taxes were too high: “They are right…this is just a retributive tax, designed not so much to encourage people to use public transport as to punish them for using cars, the 20th century’s greatest symbol of individual autonomy.” (16 September 2000).

The irony continues to sizzle on the griddle as The Spectator sarcastically predicted that Prime Minister Tony Blair would “triumph” over the protestors. “In a few days’ time, perhaps, we will hardly remember that Britain was reduced to the kind of panic-buying associated with a dearth of soap powder in cold war Eastern Europe.” How easy the job of Prime Minister must have seemed.

By coincidence I’ve also been reading “How Spies Think” by David Omand, former director of GCHQ (Penguin 2021). Reminiscing over the Cabinet Office’s 2000 AD tactics to ensure supply of fuel to essential users, Omand ruminates over the “prisoner’s dilemma” of the man in the street in situations like this. Almost as if he foresees the cause-and-effect of recent news reports, Ormand writes that when a panic sets in, even if there isn’t a real shortage, “it becomes clear that holding back is not rational benefit-maximizing behaviour. And since most people will reason the same way, inevitably we end up with long queues at the petrol pumps.”

By 12 September 2000, a combination of pickets, intimidation of drivers and panic buying had resulted in 3000 service stations closing as only 5% of fuel deliveries were made. The government invoked emergency powers to ensure essential services could keep moving.

On 13 September 2000, a scheme was announced to allow essential road users could keep moving on red diesel. Marked gasoil is diesel fuel released at a rebated rate of excise duty (currently about 14p a litre) for non-road use. Farm vehicles, trains, refrigeration units and any other non-road engines that qualify. The gasoil is marked and dyed to make sure it can’t be used to power road vehicles. As far as I can remember, at the height of the fuel blockades, the Department of Environment, Trade and Regions (as was) put out a notice saying that anyone holding stocks of red diesel could either use it in road vehicles or supply it to anyone else to use in road vehicles with no restrictions. Since stocks of red diesel were held by hundreds of regional distributors, it would be much more difficult to picket all of them, rather than the smaller number of refineries and distribution terminals.

While all this had probably been discussed at the highest levels, no-one had got round to telling the people on the ground at HM Customs and Excise (as was). If they had, the people on the ground would have told them that there were several legal and financial steps that had to be put in place before someone could roll out the red barrel.

It goes without saying - but I'll say it - that diverting red diesel to road use without permission is illegal and attracts heavy financial circumstances. It also should have gone without saying that permission is only given in exceptional circumstances - and it was up to the Commissioners - not the DETR - to give that permission.

In the space of a day, HMCE had to cobble together a scheme to ensure that the duty was paid on any diverted red diesel. It foreshadowed the speed and efficiency of last year’s Self Employed Income Support Scheme being set up – but on a much shorter timescale. While HMCE had limited email in place, a lot of the details came over by fax because it was a lot easier to get forms and bulk information transmitted that way (scanners were a dream of the future). As far as I can recall the DETR announcement came out around 11 in the morning, and the scheme was in place by 5pm that evening.

Bear in mind that in 2000, HM Customs and Excise operated out these archaic and now eradicated structures called local offices. Many of them had public counters where anyone could walk in and get a public notice or talk about their tax affairs. In some cases, it wasn’t unknown for restaurant to empty their tills, run round and pay their VAT over the counter on the day it was due.

So a scheme was set up where punters could apply for a license to use rebated gasoil as road fuel. Essential users (eg ambulance service, bus companies etc) were to be given priority. Anyone wanting to use the scheme would have to repay the rebate up front (in other words, pay over the difference between the red diesel duty and the usual road fuel duty). And they were sternly warned that they couldn’t use the red diesel until their license was issued. Bear in mind, this happened all over the country, with accounting systems being set up and procedures put in place to handle the flood of requests. In our own office I reckon maybe 50% of those who’d requested an application form were actually granted a license. Hopefully because they were able to get hold of supplies of white diesel. Of course the biggest problem was that a lot of those users held red diesel for purposes that were essential to their process. It would be no good running a refrigerated truck on red diesel as road fuel if that meant you were left without enough red diesel to power the freezer unit. And if you were a hospital, was it more important to keep your ambulances on the road or keep your generators going?

As luck would have it, nobody had to answer those questions. The fuel protests were called off the next day and by the weekend of the 16 th white diesel and petrol supplies began to return to normal. Again, the difference in 2021 is that we're already starting to hear stories about red diesel being delivered four days late. There aren't any pickets, but if there aren't enough delivery drivers to do their legal hours, it has the same effect.

The biggest legacy of the short-lived repayment scheme was that it put ideas in people’s minds. I remember the director of one local haulage firm rang up to say he’d had a brainwave. “It’d be awfully helpful for my cashflow,” he said, “If they could deliver the DERV to my tanks without duty – and then as we filled our wagons up, we could pay you the duty every week.” Sadly, his idea didn’t fly. But I can never hear the Go West single, ‘King of Wishful Thinking’ without being reminded of him.